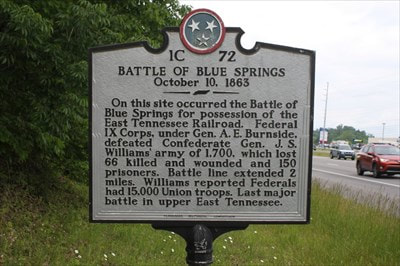

Blue Springs (October 10, 1863)

Union Major General Ambrose Burnside, commander of the Department of the Ohio, undertook an expedition into East Tennessee to clear the roads and passes to Virginia, and, if possible, secure the saltworks beyond Abingdon. In October, Confederate Brig. General John S. Williams, with his cavalry force, set out to disrupt Union communications and logistics. He wished to take Bull's Gap on the East Tennessee & Virginia Railroad.

On October 3, while advancing on Bull's Gap, he fought with Brig. General Samuel P. Carter's Union Cavalry Division, XXIII Army Corps, at Blue Springs, about nine miles from Bull's Gap, on the railroad. Carter, not knowing how many of the enemy he faced, withdrew. Carter and Williams skirmished for the next few days.

On October 10, Carter approached Blue Springs in force. Williams had received some reinforcements. The battle began about 10:00 am with Union cavalry engaging the Confederates until afternoon while another mounted force attempted to place itself in a position to cut off a Rebel retreat. Captain Orlando M. Poe, the Chief Engineer, performed a reconnaissance to identify the best location for making an infantry attack.

At 3:30 pm, Brig. General Edward Ferrero's 1st Division, IX Army Corps, moved up to attack, which he did at 5:00 pm. Ferrero's men broke into the Confederate line, causing heavy casualties, and advanced almost to the enemy's rear before being checked. After dark, the Confederates withdrew and the Federals took up the pursuit in the morning. Within days, Williams and his men had retired to Virginia.

Burnside had launched the East Tennessee Campaign to reduce or extinguish Confederate influence in the area; Blue Springs helped fulfill that mission.

Union Major General Ambrose Burnside, commander of the Department of the Ohio, undertook an expedition into East Tennessee to clear the roads and passes to Virginia, and, if possible, secure the saltworks beyond Abingdon. In October, Confederate Brig. General John S. Williams, with his cavalry force, set out to disrupt Union communications and logistics. He wished to take Bull's Gap on the East Tennessee & Virginia Railroad.

On October 3, while advancing on Bull's Gap, he fought with Brig. General Samuel P. Carter's Union Cavalry Division, XXIII Army Corps, at Blue Springs, about nine miles from Bull's Gap, on the railroad. Carter, not knowing how many of the enemy he faced, withdrew. Carter and Williams skirmished for the next few days.

On October 10, Carter approached Blue Springs in force. Williams had received some reinforcements. The battle began about 10:00 am with Union cavalry engaging the Confederates until afternoon while another mounted force attempted to place itself in a position to cut off a Rebel retreat. Captain Orlando M. Poe, the Chief Engineer, performed a reconnaissance to identify the best location for making an infantry attack.

At 3:30 pm, Brig. General Edward Ferrero's 1st Division, IX Army Corps, moved up to attack, which he did at 5:00 pm. Ferrero's men broke into the Confederate line, causing heavy casualties, and advanced almost to the enemy's rear before being checked. After dark, the Confederates withdrew and the Federals took up the pursuit in the morning. Within days, Williams and his men had retired to Virginia.

Burnside had launched the East Tennessee Campaign to reduce or extinguish Confederate influence in the area; Blue Springs helped fulfill that mission.

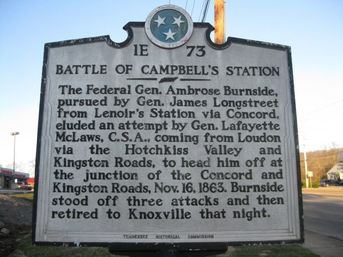

Campbell's Station (November 16, 1863)

In early November 1863, Lt. General James Longstreet, with two divisions and about 5,000 cavalry, was detached from the Confederate Army of Tennessee near Chattanooga to attack Major General Ambrose E. Burnside's Union Department of the Ohio troops at Knoxville, Tennessee.

Following parallel routes, Longstreet and Burnside raced for Campbell's Station, a hamlet where the Concord Road, from the south, intersected the Kingston Road to Knoxville. Burnside hoped to reach the crossroads first and continue on to safety in Knoxville; Longstreet planned to reach the crossroads and hold it, which would prevent Burnside from gaining Knoxville and force him to fight outside his earthworks.

By forced marching, on a rainy November 16, Major General Ambrose E. Burnside's advance reached the vital intersection and deployed first. The main column arrived at noon with the baggage train just behind. Scarcely 15 minutes later, Longstreet's Confederates approached. Longstreet attempted a double envelopment: attacks timed to strike both Union flanks simultaneously.

Major General Lafayette McLaw's Confederate division struck with such force that the Union right had to redeploy, but held. Brig. General Micah Jenkins's Confederate division maneuvered ineffectively as it advanced and was unable to turn the Union left. Burnside ordered his two divisions astride the Kingston Road to withdraw three-quarters of a mile to a ridge in their rear. This was accomplished without confusion. The Confederates suspended their attack while Burnside continued his retrograde movement to Knoxville.

Had Longstreet reached Campbell's Station first, the Knoxville Campaign's results might have been different.

In early November 1863, Lt. General James Longstreet, with two divisions and about 5,000 cavalry, was detached from the Confederate Army of Tennessee near Chattanooga to attack Major General Ambrose E. Burnside's Union Department of the Ohio troops at Knoxville, Tennessee.

Following parallel routes, Longstreet and Burnside raced for Campbell's Station, a hamlet where the Concord Road, from the south, intersected the Kingston Road to Knoxville. Burnside hoped to reach the crossroads first and continue on to safety in Knoxville; Longstreet planned to reach the crossroads and hold it, which would prevent Burnside from gaining Knoxville and force him to fight outside his earthworks.

By forced marching, on a rainy November 16, Major General Ambrose E. Burnside's advance reached the vital intersection and deployed first. The main column arrived at noon with the baggage train just behind. Scarcely 15 minutes later, Longstreet's Confederates approached. Longstreet attempted a double envelopment: attacks timed to strike both Union flanks simultaneously.

Major General Lafayette McLaw's Confederate division struck with such force that the Union right had to redeploy, but held. Brig. General Micah Jenkins's Confederate division maneuvered ineffectively as it advanced and was unable to turn the Union left. Burnside ordered his two divisions astride the Kingston Road to withdraw three-quarters of a mile to a ridge in their rear. This was accomplished without confusion. The Confederates suspended their attack while Burnside continued his retrograde movement to Knoxville.

Had Longstreet reached Campbell's Station first, the Knoxville Campaign's results might have been different.

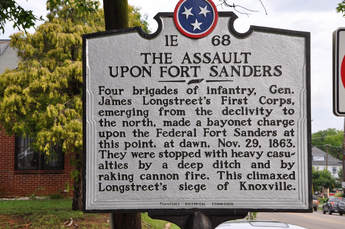

Fort Sanders (November 29, 1863)

In attempting to take Knoxville, the Confederates decided that Fort Sanders was the only vulnerable place where they could penetrate Union Major General Burnside's fortifications, which enclosed the city, and successfully conclude the siege, already a week long. The fort surmounted an eminence just northwest of Knoxville.

Northwest of the fort, the land dropped off abruptly. Confederate Lt. General James Longstreet believed he could assemble a storming party, undetected at night, below the fortifications and, before dawn, overwhelm Fort Sanders by a coup de main. Following a brief artillery barrage directed at the fort's interior, three Rebel brigades charged.

Union wire entanglements-–telegraph wire stretched from one tree stump to another to another-–delayed the attack, but the fort's outer ditch halted the Confederates. This ditch was twelve feet wide and from four to ten feet deep with vertical sides. The fort's exterior slope was almost vertical, also. Crossing the ditch was nearly impossible, especially under withering defensive fire from musketry and canister.

Confederate officers did lead their men into the ditch, but, without scaling ladders, few emerged on the scarp side and a small number entered the fort to be wounded, killed, or captured. The attack lasted a short twenty minutes. Longstreet undertook his Knoxville expedition to divert Union troops from Chattanooga and to get away from General Braxton Bragg, with whom he was engaged in a bitter feud. His failure to take Knoxville scuttled his purpose.

This was the decisive battle of the Knoxville Campaign. This Confederate defeat, plus the loss of Chattanooga on November 25, put much of East Tennessee in the Union camp.

In attempting to take Knoxville, the Confederates decided that Fort Sanders was the only vulnerable place where they could penetrate Union Major General Burnside's fortifications, which enclosed the city, and successfully conclude the siege, already a week long. The fort surmounted an eminence just northwest of Knoxville.

Northwest of the fort, the land dropped off abruptly. Confederate Lt. General James Longstreet believed he could assemble a storming party, undetected at night, below the fortifications and, before dawn, overwhelm Fort Sanders by a coup de main. Following a brief artillery barrage directed at the fort's interior, three Rebel brigades charged.

Union wire entanglements-–telegraph wire stretched from one tree stump to another to another-–delayed the attack, but the fort's outer ditch halted the Confederates. This ditch was twelve feet wide and from four to ten feet deep with vertical sides. The fort's exterior slope was almost vertical, also. Crossing the ditch was nearly impossible, especially under withering defensive fire from musketry and canister.

Confederate officers did lead their men into the ditch, but, without scaling ladders, few emerged on the scarp side and a small number entered the fort to be wounded, killed, or captured. The attack lasted a short twenty minutes. Longstreet undertook his Knoxville expedition to divert Union troops from Chattanooga and to get away from General Braxton Bragg, with whom he was engaged in a bitter feud. His failure to take Knoxville scuttled his purpose.

This was the decisive battle of the Knoxville Campaign. This Confederate defeat, plus the loss of Chattanooga on November 25, put much of East Tennessee in the Union camp.

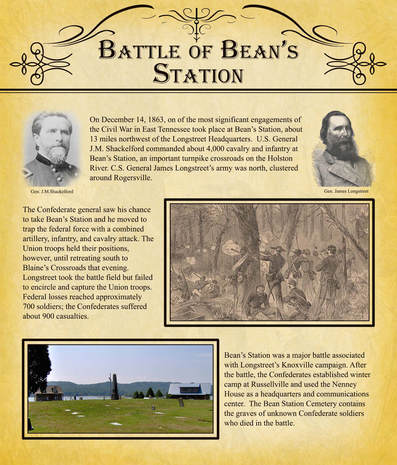

Bean's Station (December 14, 1863)

CSA Lt. General James Longstreet abandoned the Siege of Knoxville, on December 4, 1863, and retreated northeast towards Rogersville, Tennessee. Union Major General John G. Parke pursued the Confederates but not too closely. General Longstreet continued to Rutledge on December 6 and Rogersville on the 9th.

Parke sent Brig. General J.M Shackelford on with about 4,000 cavalry and infantry to search for Longstreet. On the 13th, Shackelford was near Bean's Station on the Holston River. Longstreet decided to go back and capture Bean's Station. Three Confederate columns and artillery approached Bean's Station to catch the federals in a vice. By 2:00 am on the 14th, one column was skirmishing with Union pickets. The pickets held out as best they could and warned Shackelford of the Confederate presence. He deployed his force for an assault.

Soon, the battle started and continued throughout most of the day. Confederate flanking attacks and other assaults occurred at various times and locations, but the Federals held until southern reinforcements tipped the scales. By nightfall, the Federals were retiring from Bean's Station through Bean's Gap and on to Blain's Cross Roads. Longstreet set out to attack the Union forces again the next morning, but as he approached them at Blain's Cross Roads, he found them well-entrenched.

Longstreet withdrew and the Federals soon left the area. The Knoxville Campaign ended following the battle of Bean's Station. Longstreet soon went into winter quarters at Russellville.

CSA Lt. General James Longstreet abandoned the Siege of Knoxville, on December 4, 1863, and retreated northeast towards Rogersville, Tennessee. Union Major General John G. Parke pursued the Confederates but not too closely. General Longstreet continued to Rutledge on December 6 and Rogersville on the 9th.

Parke sent Brig. General J.M Shackelford on with about 4,000 cavalry and infantry to search for Longstreet. On the 13th, Shackelford was near Bean's Station on the Holston River. Longstreet decided to go back and capture Bean's Station. Three Confederate columns and artillery approached Bean's Station to catch the federals in a vice. By 2:00 am on the 14th, one column was skirmishing with Union pickets. The pickets held out as best they could and warned Shackelford of the Confederate presence. He deployed his force for an assault.

Soon, the battle started and continued throughout most of the day. Confederate flanking attacks and other assaults occurred at various times and locations, but the Federals held until southern reinforcements tipped the scales. By nightfall, the Federals were retiring from Bean's Station through Bean's Gap and on to Blain's Cross Roads. Longstreet set out to attack the Union forces again the next morning, but as he approached them at Blain's Cross Roads, he found them well-entrenched.

Longstreet withdrew and the Federals soon left the area. The Knoxville Campaign ended following the battle of Bean's Station. Longstreet soon went into winter quarters at Russellville.

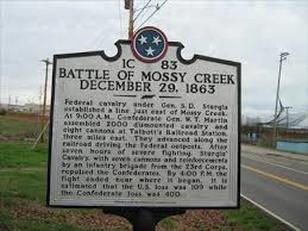

Mossy Creek (December 29, 1863)

Brig. General Samuel D. Sturgis received a report on the night of December 28, 1863, that a brigade of enemy cavalry was in the neighborhood of Dandridge that afternoon. Surmising that the Rebel cavalry force was split, Sturgis decided to meet and defeat, and possibly capture, this portion of it. He ordered most of his troopers out toward Dandridge on two roads.

After these troops had left, Major General William T. Martin, commander of General Longstreet's Confederate cavalry, now reunited, attacked the remainder of Sturgis's force at Mossy Creek, Tennessee, which included the First Brigade, Second Division, XXIII Army Corps, commanded by Col. Samuel R. Mott, at 9:00 am.

First, Sturgis sent messages to his subordinates on the way to Dandridge to return promptly if they found no enemy there. The Confederates advanced, driving the Federals in front of them. Some of the Union troopers who had set out for Dandridge returned. Around 3:00 pm, fortunes changed as the Federals began driving the Confederates. By dark, the Rebels were back to the location from which they had begun the battle.

Union pursuit was not mounted that night, but Martin retreated from the area. After the victory at Mossy Creek, the Union held the line about Talbott's Station for some time.

Brig. General Samuel D. Sturgis received a report on the night of December 28, 1863, that a brigade of enemy cavalry was in the neighborhood of Dandridge that afternoon. Surmising that the Rebel cavalry force was split, Sturgis decided to meet and defeat, and possibly capture, this portion of it. He ordered most of his troopers out toward Dandridge on two roads.

After these troops had left, Major General William T. Martin, commander of General Longstreet's Confederate cavalry, now reunited, attacked the remainder of Sturgis's force at Mossy Creek, Tennessee, which included the First Brigade, Second Division, XXIII Army Corps, commanded by Col. Samuel R. Mott, at 9:00 am.

First, Sturgis sent messages to his subordinates on the way to Dandridge to return promptly if they found no enemy there. The Confederates advanced, driving the Federals in front of them. Some of the Union troopers who had set out for Dandridge returned. Around 3:00 pm, fortunes changed as the Federals began driving the Confederates. By dark, the Rebels were back to the location from which they had begun the battle.

Union pursuit was not mounted that night, but Martin retreated from the area. After the victory at Mossy Creek, the Union held the line about Talbott's Station for some time.

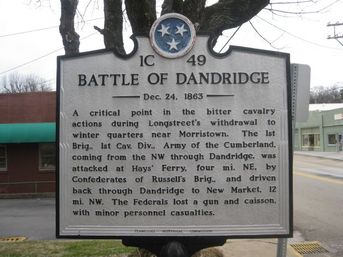

Dandridge (January 17, 1864)

Union forces under Major General John G. Parke advanced on Dandridge, Tennessee, near the East Tennessee & Virginia Railroad, on January 14, forcing Lt. General James Longstreet's Confederate troops to fall back. Longstreet, however, moved additional troops into the area on the 15th to meet the enemy and threaten the Union base at New Market.

On the 16th, Brig. General Samuel D. Sturgis, commanding the Cavalry Corps, Army of the Ohio, rode forward to occupy Kimbrough's Crossroads. Within three or four miles of his objective, Sturgis's cavalry met Rebel troops, forcing them back towards the crossroads. As the Union cavalry neared the crossroads, they discovered an enemy infantry division with artillery that had arrived the day before.

The Union cavalry could not dislodge these Rebels and was compelled to retire to Dandridge. About noon the next day, Sturgis received information that the Confederates were preparing for an attack so he formed his men into line of battle. About 4:00 pm, the Confederates advanced and the fighting quickly became general. The battle continued until after dark with the Federals occupying about the same battle line as when the fighting started.

The Union forces fell back to New Market and Strawberry Plains during the night, but the Rebels were unable to pursue because of the lack of cannons, ammunition, and shoes. For the time being, the Union forces left the area.

Union forces under Major General John G. Parke advanced on Dandridge, Tennessee, near the East Tennessee & Virginia Railroad, on January 14, forcing Lt. General James Longstreet's Confederate troops to fall back. Longstreet, however, moved additional troops into the area on the 15th to meet the enemy and threaten the Union base at New Market.

On the 16th, Brig. General Samuel D. Sturgis, commanding the Cavalry Corps, Army of the Ohio, rode forward to occupy Kimbrough's Crossroads. Within three or four miles of his objective, Sturgis's cavalry met Rebel troops, forcing them back towards the crossroads. As the Union cavalry neared the crossroads, they discovered an enemy infantry division with artillery that had arrived the day before.

The Union cavalry could not dislodge these Rebels and was compelled to retire to Dandridge. About noon the next day, Sturgis received information that the Confederates were preparing for an attack so he formed his men into line of battle. About 4:00 pm, the Confederates advanced and the fighting quickly became general. The battle continued until after dark with the Federals occupying about the same battle line as when the fighting started.

The Union forces fell back to New Market and Strawberry Plains during the night, but the Rebels were unable to pursue because of the lack of cannons, ammunition, and shoes. For the time being, the Union forces left the area.

Fair Garden (January 27, 1864)

Since the Battle of Dandridge, the Union cavalry had moved to the south side of the French Broad River and had disrupted Confederate foraging and captured numerous wagons in that area. On January 25, 1864, Lt. General James Longstreet, commander of the Department of East Tennessee, instructed his subordinates to do something to curtail Union operations south of the French Broad.

On the 26th, Brig. General Samuel D. Sturgis, having had various brushes with Confederate cavalry, deployed his troopers to watch the area fords. Two Confederate cavalry brigades and artillery advanced from Fair Garden in the afternoon but were checked about four miles from Sevierville. Other Confederates attacked a Union cavalry brigade, though, at Fowler's on Flat Creek, and drove it about two miles.

No further fighting occurred that day. Union scouts observed that the Confederates had concentrated on the Fair Garden Road, so Sturgis ordered an attack there in the morning. In a heavy fog, Col. Edward M. McCook's Union division attacked and drove back Major General William T. Martin's Confederates until about 4:00 pm. At that time, McCook's men charged with sabers and routed the Rebels.

Sturgis set out in pursuit on the 28th, and captured and killed more of the routed Rebels. The Union forces, however, observed three of Longstreet's infantry brigades crossing the river. Realizing his weariness from fighting, lack of supplies, ammunition, and weapons and the overwhelming strength of the enemy, Sturgis decided to evacuate the area. But, before leaving, Sturgis determined to attack Brig. General Frank C. Armstrong's Confederate cavalry division which he had learned was about three or four miles away, on the river.

Unbeknownst to the attacking Federals, Armstrong had strongly fortified his position and three infantry regiments had arrived to reinforce him. Thus, the Union troops suffered severe casualties in the attack. The battle continued until dark, when the Federals retired from the area.

The Federals had won the big battle but the fatigue of continual fighting and lack of supplies and ammunition forced them to withdraw.

Since the Battle of Dandridge, the Union cavalry had moved to the south side of the French Broad River and had disrupted Confederate foraging and captured numerous wagons in that area. On January 25, 1864, Lt. General James Longstreet, commander of the Department of East Tennessee, instructed his subordinates to do something to curtail Union operations south of the French Broad.

On the 26th, Brig. General Samuel D. Sturgis, having had various brushes with Confederate cavalry, deployed his troopers to watch the area fords. Two Confederate cavalry brigades and artillery advanced from Fair Garden in the afternoon but were checked about four miles from Sevierville. Other Confederates attacked a Union cavalry brigade, though, at Fowler's on Flat Creek, and drove it about two miles.

No further fighting occurred that day. Union scouts observed that the Confederates had concentrated on the Fair Garden Road, so Sturgis ordered an attack there in the morning. In a heavy fog, Col. Edward M. McCook's Union division attacked and drove back Major General William T. Martin's Confederates until about 4:00 pm. At that time, McCook's men charged with sabers and routed the Rebels.

Sturgis set out in pursuit on the 28th, and captured and killed more of the routed Rebels. The Union forces, however, observed three of Longstreet's infantry brigades crossing the river. Realizing his weariness from fighting, lack of supplies, ammunition, and weapons and the overwhelming strength of the enemy, Sturgis decided to evacuate the area. But, before leaving, Sturgis determined to attack Brig. General Frank C. Armstrong's Confederate cavalry division which he had learned was about three or four miles away, on the river.

Unbeknownst to the attacking Federals, Armstrong had strongly fortified his position and three infantry regiments had arrived to reinforce him. Thus, the Union troops suffered severe casualties in the attack. The battle continued until dark, when the Federals retired from the area.

The Federals had won the big battle but the fatigue of continual fighting and lack of supplies and ammunition forced them to withdraw.

Bull's Gap (November 11-13, 1864)

In November 1864, Major General John C. Breckinridge undertook an expedition into East Tennessee, anticipating that Confederate sympathizers would join his force and help drive the Yankees from the area. The Federals initially retired in front of this force and, on November 10, were at Bull's Gap on the East Tennessee & Virginia Railroad.

The Confederates attacked them on the morning of the 11th but were repulsed by 11:00 am. Artillery fire continued throughout the day. The next morning, both sides attacked; the Confederates sought to hit the Union forces in a variety of locations but they gained little. The next day firing occurred throughout most of the day, but the Confederates did not assault the Union lines because they were marching to flank them on the right.

Before making the flank attack, the Union forces, short on everything from ammunition to rations, withdrew from Bull's Gap after midnight on the 4th. Breckinridge pursued, but the Federals received reinforcements and foul weather played havoc with the roads and streams. Breckinridge, with most of his force, retired back to Virginia.

This victory was a temporary Union setback in the Federal plans to rid East Tennessee of Confederate influence.

In November 1864, Major General John C. Breckinridge undertook an expedition into East Tennessee, anticipating that Confederate sympathizers would join his force and help drive the Yankees from the area. The Federals initially retired in front of this force and, on November 10, were at Bull's Gap on the East Tennessee & Virginia Railroad.

The Confederates attacked them on the morning of the 11th but were repulsed by 11:00 am. Artillery fire continued throughout the day. The next morning, both sides attacked; the Confederates sought to hit the Union forces in a variety of locations but they gained little. The next day firing occurred throughout most of the day, but the Confederates did not assault the Union lines because they were marching to flank them on the right.

Before making the flank attack, the Union forces, short on everything from ammunition to rations, withdrew from Bull's Gap after midnight on the 4th. Breckinridge pursued, but the Federals received reinforcements and foul weather played havoc with the roads and streams. Breckinridge, with most of his force, retired back to Virginia.

This victory was a temporary Union setback in the Federal plans to rid East Tennessee of Confederate influence.

Russellville/Morristown (November 12, 1864)

Following a failed Confederate assault on Bull’s Gap by troops under Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge on 12 November 1864, the Union commander in the Gap, Brig. Gen. Alvan C. Gillem, determined to evacuate the Gap the next night. Alert Confederate scouts noticed when Union troops abandoned Taylor’s Gap southwest of Gillem’s position, a fact they immediately reported to Breckinridge and his second-in-command, Brig. Gen. Basil Duke. Breckinridge hoped to find Gillem strung out on the road to Russellville and pushed his troops through Taylor’s Gap and rushed to Russellville on the Warrensburg/Arnott Road. Gillem, moving up to Whitesburg on a parallel turnpike and hearing that Union reinforcements had arrived at Morristown, sent word for the new troops to meet him in Russellville. There, he placed two battalions of dismounted cavalry in separate supporting positions in case the initial line was overrun. At 1 a.m. on November 14, Breckinridge attacked Gillem’s Union battalions in Russellville and sent them reeling west towards Morristown, capturing many prisoners in the woods. The second line of troops held the charging Confederates until ammunition ran low. At that point, the entire Union force streamed back to Morristown, where it rallied behind the new regiment sent to reinforce them. After capturing a single artillery piece on a knoll, rampaging Confederates broke the Federal line once more. This time, pursuing cavalrymen chased Union survivors all the way back to Strawberry Plains, a distance of 25 miles. Gillem, separated from his troops during the charge, made his way to the Plains by a side road and rejoined his shattered command, minus several hundred men lost mostly to capture.

Following a failed Confederate assault on Bull’s Gap by troops under Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge on 12 November 1864, the Union commander in the Gap, Brig. Gen. Alvan C. Gillem, determined to evacuate the Gap the next night. Alert Confederate scouts noticed when Union troops abandoned Taylor’s Gap southwest of Gillem’s position, a fact they immediately reported to Breckinridge and his second-in-command, Brig. Gen. Basil Duke. Breckinridge hoped to find Gillem strung out on the road to Russellville and pushed his troops through Taylor’s Gap and rushed to Russellville on the Warrensburg/Arnott Road. Gillem, moving up to Whitesburg on a parallel turnpike and hearing that Union reinforcements had arrived at Morristown, sent word for the new troops to meet him in Russellville. There, he placed two battalions of dismounted cavalry in separate supporting positions in case the initial line was overrun. At 1 a.m. on November 14, Breckinridge attacked Gillem’s Union battalions in Russellville and sent them reeling west towards Morristown, capturing many prisoners in the woods. The second line of troops held the charging Confederates until ammunition ran low. At that point, the entire Union force streamed back to Morristown, where it rallied behind the new regiment sent to reinforce them. After capturing a single artillery piece on a knoll, rampaging Confederates broke the Federal line once more. This time, pursuing cavalrymen chased Union survivors all the way back to Strawberry Plains, a distance of 25 miles. Gillem, separated from his troops during the charge, made his way to the Plains by a side road and rejoined his shattered command, minus several hundred men lost mostly to capture.